Not every penguin breeds every year!

Some fail early, either through inexperience, bird predation or weather. Others may arrive in poor condition after a hard winter. Regardless of the reason why, nonbreeding adult birds can make up a substantial proportion of a colony and they will likely contribute to the breeding population in subsequent years. However as nonbreeders they have no need to return from sea to feed dependent chicks, and can potentially travel to more favourable foraging grounds at sea and remain feeding for longer periods that breeding conspecifics.

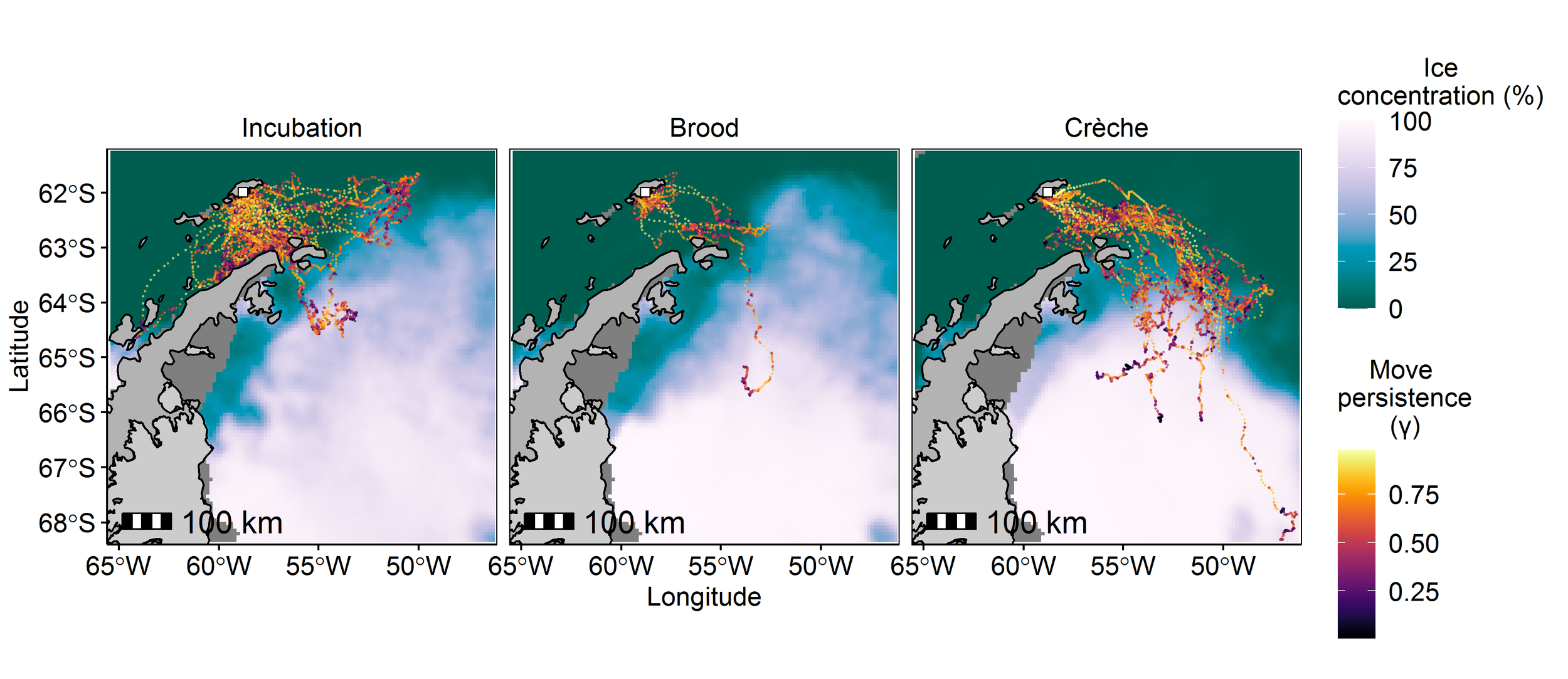

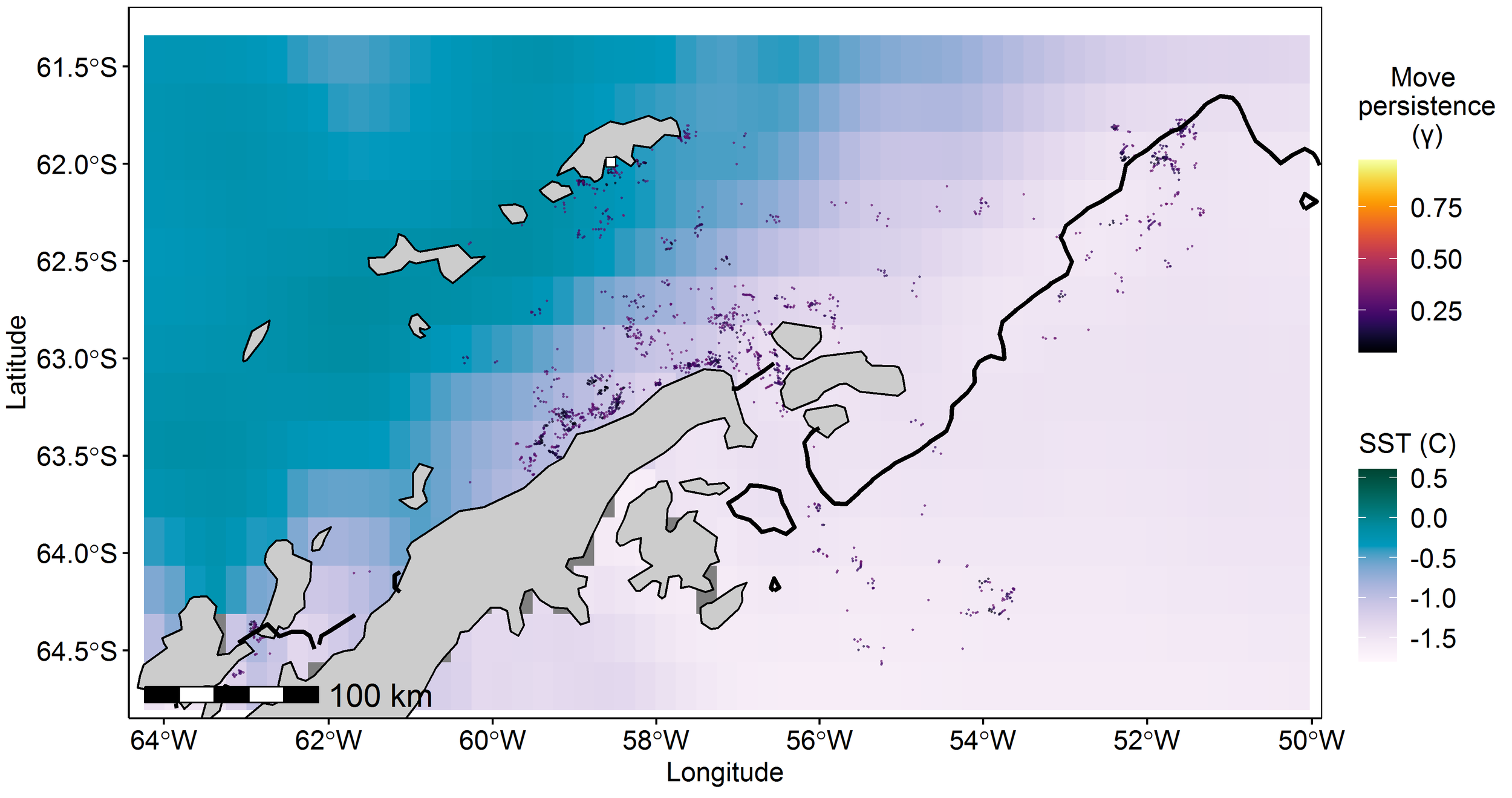

We see whether this is the case, by comparing the foraging behaviour of nonbreeding and breeding adult Adelie penguins from the South Shetland Islands during the breeding season (austral summer). Nonbreeding birds behaved differently to breeders, preferring to feed in the colder waters off the coast of the Peninsula rather than in the comparatively warmer waters of the northern Bransfield. Their larger foraging ranges during the chick-rearing stage of the breeding season also meant they can overlap with those of breeding birds from other colonies (intraspecific competition) or with other krill-foraging breeding penguins (interspecific competition). Ultimately when using marine predators such as penguins as “sentinel species”, the behaviours of nonbreeders should be considered fully to correctly interpret the signals they are providing about the ecosystem, especially in the context of environmental management.

“Conducting this project as a collaborative effort between South Africa, Argentina, Poland, the US and Norway has resulted in a first in terms of ecological research into meso-predator foraging ecology.”, says lead author Dr Chris Oosthuizen, University of Pretoria, South Africa

“I think it is long overdue that different life history stages of monitored species are considered when using marine predators as sentinel species. When we interpret what breeding stages of monitored species are telling us, we need to interpret it in the context of inter and intra specific competition with those monitored animals. This work adds another important piece to the puzzle of understanding how the marine ecosystem functions., says Dr Andy Lowther , NPI. Norway.